I remember seeing a Frederick Church (1826-1900) painting of icebergs fifteen years ago. Church had sailed north to sketch them and then later painted them in his studio. I wondered what the real colors would look like, and ever since then, I thought about someday painting icebergs myself.

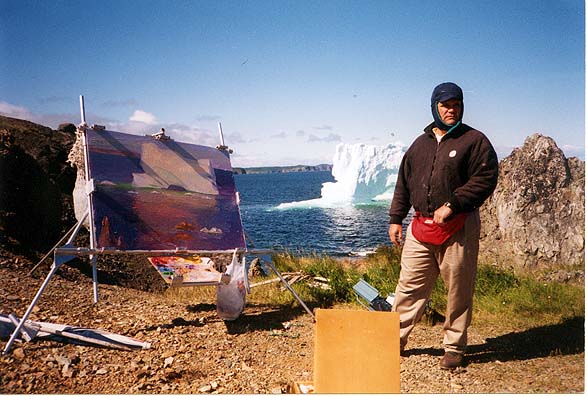

I knew the challenge of such a project required special planning, including finding an easel capable of surviving extreme conditions. So before I started out, my fisherman friend John Finneran custom built an easel for me; it's a go-anywhere, under-any-conditions painting tool.

After months of planning and constructing, and despite some loose ends, on Monday morning, July 11, I drove my car and equiptment fourteen hours northeast to Cape Breton, Nova Scotia, where some friends of mine had rented a farm. I spent a week there painting the Bras d'Or Lakeand testing the easel, waiting for news of ice. On July 14, I got word of an iceberg spotted in a cove on the northeast coast in the town of Twillingate, Newfoundland. It was still four hours drive to the eight-hour ferry trip across the Cabot Strait to Port-a-Basque. The ferry captain told me of the sometimes treacherous autumn crossing on fifty-foot waves, and as I drove from the ferry, with still another ten hours of road ahead of me, I vowed to be off the big island of Newfoundland by autumn.

Upon arriving at Twillingate, I found ice - looming ahead, just offshore, a giant grounded iceberg. It was over one hundred yards beyond a forty-foot cliff, but so big, I felt I could touch it. I unloaded my easel, mounted a "36x48" panel to it, punched oil paint out of the oversized tubes of color onto the palette while grabbing my painting knife to begin painting what would become I of VI.

Nearly two hours into the work, I heard loud cracks from the iceberg, like a group of musket shots with echoes. A huge piece of ice broke off the face with a crashing explosion. Six-foot waves of ice flotsam circled outward several minutes for two hundred yards. And the colors I saw - emerald, azure, translucent cream, almost dirty in appearence, deep aqua and cobalt - colors caused by thousands of years and tons of pressure. How was I going to paint this huge strange color mass disintergrating in front of my eyes? I thought of how long I had yearned for such an opportunity, the months of planning and preparation, and the several thousand dollars of expense, and said to myself, "All that and only a few moments to paint?" The dread and exhilaration buckled my knees.

Even with gusts of twenty knots or more and my 4' panel up in the wind like a sail, the easel performed beautifully like the Rock of Gibraltar. I never lost focus or concentration because I knew the wind could not blow my work off the cliff.

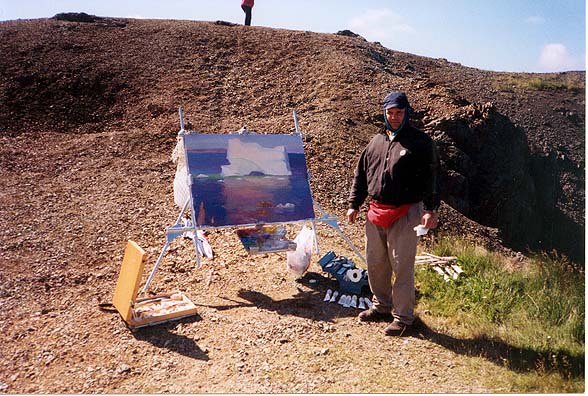

The next day, overnight melting and break up caused an arch to form at the base. The full sun at my back and straight into the front plane of the iceberg, created an iridescent and unbelievably high-keyed orange color, which contrasted the magenta and cerulean sky. I struggle to depict the light, but when it was too different in color to even think of continuing, I mounted a new panel and began painting the iceberg for the third time. This time I moved over the craggy rocks until I found an angle that made the iceberg look like the Flying Dutchman.

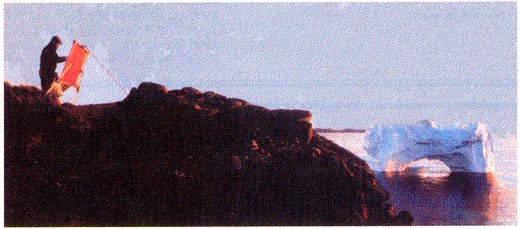

With an acute pain in my arm and shoulder from painting so furiously, I packed up to eat and rest. I returned that day to paint it in the late-day sun. By that time, the arch had grown larger under the center of the iceberg, curving nearly half way up the iceberg. It left two turrets on either side and appeared medieval silhouetted against the long northern sunset. Despite searing arm pain and fading light I continued to paint. Just after I stopped, the loudest explosion I'd heard yet signaled the total rending of the giant iceberg in two. It split apart amid a small tidle wave. The biggest resulting chunk was was so much lighter than the original that it began to slowly rise up and come free-a separate piece as big as the first. I watched incredulously as the ringlets of surf rhythmically subsided. It had flipped over one hundred eighty degrees. The underwater part-now on top-had surreal shapes carved out of its bottom by the Labrador Current. I've never seen such shapes and colors. The still large "bergie bit", as Newfoundlanders call pieces of left over icebergs, began to settle and float away, along with my hopes of continuing the work. It was less than two days since I arrived. At least it waited until I stopped work on hte fourth painting, IV of VI.

Szarek on the Island of Twillingate, Newfoundland

I hauled everything back to my cabin a few miles away to take stock of events and nurse my arm. On the morning of the third day, I spoke to some local men who saw the iceberg less than two miles down the coast, and my hopes rose. I found it floating adrift, moving very slowly. I had no idea how I would paint it on the move, but I set up anyway. The wind was strong. For the first time I needed to secure the easel by hanging a net-bag full of rocks from the back leg. I'd never been able to paint in wind that fierce. By shifting my easel frequently, I was able to paint V of VI. By that time the iceberg had drifted to points inaccessible to me. I thought it was over.

After sightseeing that day, late in the afternoon, I was looking out from a rise about five miles from the first painting site. In a cove I saw the last bit of the iceberg, caught on an out-crop of land, a lone white spot in the landscape. I painted one last time until dusk. Painting VI of VI really was the end. It had been less than three days and I had six large paintings of a single icebergs demise.

I'll go anywhere in the world to paint. My arm still bothers me a little but like my easel, I'm ready.